Buddhas of Bamiyan

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

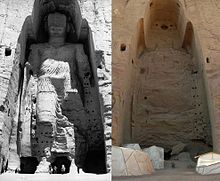

Larger 55-metre (180 ft) "Western Buddha" Smaller 38-metre (125 ft) "Eastern Buddha" Pictures of the two Buddhas before they were destroyed by the Taliban in March 2001. Carbon dating determined that the Western Buddha was built around 591–644 CE and that the Eastern Buddha was built around 544–595 CE.[1][2] | |

| Location | Bamiyan, Afghanistan |

| Part of | Cultural Landscape and Archaeological Remains of the Bamyan Valley |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, iv, vi. |

| Reference | 208-001 |

| Inscription | 2003 (27th Session) |

| Endangered | 2003–present |

| Area | 105 ha |

| Buffer zone | 225.25 ha |

| Coordinates | 34°49′55″N 67°49′36″E / 34.8320°N 67.8267°E |

The Buddhas of Bamiyan (Pashto: د باميانو بودايي پژۍ, Dari: تندیسهای بودا در بامیان) were two possibly 6th-century[3] monumental Buddhist statues in the Bamiyan Valley of Afghanistan. Located 130 kilometres (81 mi) to the northwest of Kabul, at an elevation of 2,500 metres (8,200 ft), carbon dating of the structural components of the Buddhas has determined that the smaller 38 m (125 ft) "Eastern Buddha" was built around 570 CE, and the larger 55 m (180 ft) "Western Buddha" was built around 618 CE, which would date both to the time when the Hephthalites ruled the region.[2][4][5] As a UNESCO World Heritage Site of historical Afghan Buddhism, it was a holy site for Buddhists on the Silk Road.[6] However, in March 2001, both statues were destroyed by the Taliban following an order given on February 26, 2001, by Taliban leader Mullah Muhammad Omar, to destroy all the statues in Afghanistan "so that no one can worship or respect them in the future".[7] International and local opinion condemned the destruction of the Buddhas.[8]

The statues represented a later evolution of the classic blended style of Greco-Buddhist art at Gandhara.[9] The larger statue was named "Salsal" ("the light shines through the universe") and was referred as a male. The smaller statue is called "Shah Mama" ("Queen Mother") and is considered as a female figure.[10] But it is unsure. They have made the smaller statue first, then the larger one.[11] Technically, both were reliefs: at the rear, they each merged into the cliff wall. The main bodies were hewn directly from the sandstone cliffs, but details were modeled in mud mixed with straw, coated with stucco. This coating, the majority of which wore away long ago, was painted to enhance the expressions of the faces, hands, and folds of the robes; the larger one was painted carmine red, and the smaller one was painted multiple colours.[12] The lower parts of the statues' arms were constructed from the same mud-straw mix, supported on wooden armatures. It is believed that the upper parts of their faces consisted of huge wooden masks.[2]

Since the 2nd century CE, Bamiyan had been a Buddhist religious site on the Silk Road under the Kushans, remaining so until the Islamic conquests of 770 CE, and finally coming under the Turkic Ghaznavid rule in 977 CE.[1] In 1221, Genghis Khan invaded the Bamiyan Valley, wiping out most of its population but leaving the Bamiyan Buddhas undamaged.[13][14] Later in the 17th century, Mughal emperor Aurangzeb briefly ordered the use of artillery to destroy the statues, causing some damage, though the Buddhas survived without any major harm.[14][15][16]

The Buddhas had been surrounded by numerous caves and surfaces decorated with paintings.[17] It is thought that these mostly dated from the 6th to 8th centuries CE and had come to an end with the Muslim conquests of Afghanistan.[17] The smaller works of art are considered as an artistic synthesis of Buddhist art and Gupta art from ancient India, with influences from the Sasanian Empire and the Byzantine Empire, as well as the Tokhara Yabghus.[17]

History

[edit]

Commissioning

[edit]

Bamiyan lies on the Silk Road, which runs through the Hindu Kush mountain region in the Bamiyan Valley. The Silk Road has been historically a caravan route linking the markets of China with those of the Western world. It was the site of several Buddhist monasteries, and a thriving center for religion, philosophy, and art. Monks at the monasteries lived as hermits in small caves carved into the side of the Bamyan cliffs. Most of these monks embellished their caves with religious statuary and elaborate, brightly colored frescoes, sharing the culture of Gandhara.

The Great Buddhas of Bamiyan were built around 600 CE during the time of the Hephthalites, who ruled as principalities in the areas of Tokharistan and northern Afghanistan.[4][19] However it must be noted that the Hephthalites did not always follow the Buddhist faith. For instance, during the time of Song Yun, who visited the chief of the Hephthalite nomads at his summer residence in Badakhshan and later in Gandhara, observed that they had no belief in the Buddhist law and served a large number of divinities."[20] Regardless, Bamiyan had been a Buddhist religious site since the 2nd century CE under the Kushans, and remained so up to the time of the Muslim conquest of the Abbasid Caliphate under Al-Mahdi in 770 CE. It became again Buddhist from 870 CE until the final Islamic conquest of 977 CE under the Turkic Ghaznavid dynasty.[1] Murals in the adjoining caves have been carbon dated from 438 to 980 CE, suggesting that Buddhist artistic activity continued down to the final occupation by the Muslims.[1]

The two most prominent statues were the giant standing sculptures of the Buddhas Vairocana and Sakyamuni (Gautama Buddha), identified by the different mudras performed. The Buddha popularly called "Solsol" measured 55 meters tall, and "Shahmama" 38 meters. The niches in which the figures stood are 58 and 38 meters respectively from bottom to top.[21][22] Before being blown up in 2001, they were the largest examples of standing Buddha carvings in the world (the 8th century Leshan Giant Buddha is taller,[23] but is sitting).

Following the destruction of the statues in 2001, carbon dating of organic internal structural components found in the rubble has determined that the two Buddhas were built c. 600 CE, with narrow dates of between 544 and 595 CE for the 38-meter Eastern Buddha, and between 591 and 644 CE for the larger Western Buddha.[1] Recent scholarship has also been giving broadly similar dates based on stylistic and historical analysis, although the similarities with the Art of Gandhara had generally encouraged an earlier dating in older literature.[1]

Historic documentation refers to celebrations held every year attracting numerous pilgrims, with offers being made to the monumental statues.[24] They were perhaps the most famous cultural landmarks of the region, and the site was listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site along with the surrounding cultural landscape and archaeological remains of the Bamyan Valley. Their colour faded through time.[25]

Pre-modern era

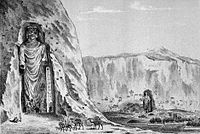

[edit]Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang visited the site on 30 April 630,[26][27][28] and described Bamyan in the Da Tang Xiyu Ji as a flourishing Buddhist center "with more than ten monasteries and more than a thousand monks". He also noted that both Buddha figures were "decorated with gold and fine jewels" (Wriggins, 1995). Intriguingly, Xuanzang mentions a third, even larger, reclining statue of the Buddha.[12][28] A monumental seated Buddha, similar in style to those at Bamyan, still exists in the Bingling Temple caves in China's Gansu province.

-

Engraving of the Buddhas, 19th century

-

Local men standing near the larger "Salsal" Buddha statue, c. 1940

-

Photographed by Françoise Foliot

-

Smaller, 38 meter Buddha in 1977

-

Possible reconstitution of the original appearance of the Western Buddha

-

Bamiyan themed postage stamp (1951) issued by Postes Afghanes (Afghan Post)

Mural paintings

[edit]The Buddhas are surrounded by numerous caves and surfaces decorated with paintings.[17] It is thought that the period of florescence was from the 6th to 8th century CE, until the onset of Islamic invasions.[17] These works of art are considered as an artistic synthesis of Buddhist art and Gupta art from India, with influences from the Sasanian Empire and the Byzantine Empire, as well as the country of Tokharistan.[17] The later paintings are attributable to the "Turk period" (7th–9th century CE).[29]

Eastern Buddha (built c. 544–595 CE)

[edit](7th century CE)

Most of the surfaces in the niche housing the Buddha must have been decorated with colourful murals, surrounding the Buddha with many paintings, but only fragments were remaining in modern times. For the 38 meter Eastern Buddha, built between 544 and 595 CE, the main remaining murals were the ones on the ceiling, right above the head of the Buddha. Recent dating based on stylistic and historical analysis confirms dates for these mural which follow the carbon-rated dates for the construction of the Buddhas themselves: the murals of the Eastern Buddha have been dated to the 6th to 8th century CE by Klimburg-Salter (1989), and post 635/645 CE by Tanabe (2004).[1] As late as 2002, Marylin Martin Rhie argued a 3rd–4th century date for the Eastern Buddha, based on artistic criteria.[33]

Sun God

[edit]Among the most famous paintings of the Buddhas of Bamiyan, the ceiling of the smaller Eastern Buddha represents a solar deity on a chariot pulled by horses, as well as ceremonial scenes with royal figures and devotees.[30] The god is wearing a caftan in the style of Tokhara, boots, and is holding a lance.[34] His representation is derived from the iconography of the Iranian god Mithra, as revered in Sogdia.[34] He is riding a two-wheeled golden chariot, pulled by four horses.[34] Two winged attendants are standing to the side of the charriot, wearing a Corinthian helmet with a feather, and holding a shield.[34] In the top portion are wind gods, flying with a scarf held in both hands.[34] This composition is unique, and distinct from Gandhara or India, but there are some similarities with the paintings of Kizil and Dunhuang.[34]

The central image of the Sun God on his golden chariot is framed by two lateral rows of individuals: kings and dignitaries mingling with Buddhas and Bodhisattvas.[32] One of the personages, standing behind a monk in profile, is likely the King of Bamyan.[32] He wears a crenulated crown with single crescent and korymbos, a round-neck tunic and a Sasanian headband.[32]

Hephthalite donors

[edit]The Bamiyan Buddhas were built at the time of the Hephthalites.[5] Several of the figures have the characteristic appearance of the Hephthalites of Tokharistan, with belted jackets with a unique lapel of their tunic being folded on the right side, the cropped hair, the hair accessories, their distinctive physiognomy and their round beardless faces.[32][35] These figures must represent the donors and potentates who supported the building of the monumental giant Buddha.[32] The individuals in this painting are very similar to the individuals depicted in Balalyk Tepe, and they may be related to the Hepthalites.[36][37] They participate "to the artistic tradition of the Hephthalite ruling classes of Tukharestan".[37]

These murals disappeared with the destructions of 2001.[32]

-

Probable Hepthalite rulers of Tokharistan, with single-lapel caftan and single-crescent crown, in the lateral row of dignitaries next to the Sun God.[35][36][32]

Western Buddha (built c. 591–644 CE)

[edit]A few murals also remained around the taller 55 meter Western Buddha on the ceiling and on the sides. Many are more conventionally Buddhist in character. Some of the later mural paintings show male devotees in double-lapel caftans.[39]

-

Paintings of celestial beings in the niche of the 55 meter large Buddha.

-

Western Buddha, Niche, ceiling, east section E1 and E2.[40]

-

Bodhisattva, ceiling of the niche of the Great Western Buddha, early 7th century, Bamiyan

-

Devotee in double-lapel caftan, left wall of the niche of the Western Buddha.[40][41] He has also been described as a Hephthalite.[42]

Adjoining caves

[edit]Later mural paintings of Bamiyan, dated to the 7th–8th centuries CE, display a variety of male devotees in double-lapel caftans.[39] The works of art show a sophistication and cosmopolitanism comparable to other works of art of the Silk Road, such as those of Kizil, are attributable to the sponsorship of the Western Turks (Yabghus of Tokharistan).[39] The nearby Kakrak caves also have some works of art.

-

Bodhisattva Maitreya, ceiling of the cave E, late 7th early 8th century, Bamiyan

-

Buddha wearing a crown and a chamail cape. Painting in niche "I" at Bamiyan, 7th century CE

-

Devotee in double-lapel caftan, next to the Buddha. Cave G, Bamyan (detail)

-

Reconstructed mural of Cave G, Bamyan

After the destruction of the Buddhas, 50 more caves were revealed. In 12 of the caves, wall paintings were discovered.[43] In December 2004, an international team of researchers stated that the wall paintings at Bamyan were painted between the 5th and the 9th centuries, rather than the 6th to 8th centuries, citing their analysis of radioactive isotopes contained in straw fibers found beneath the paintings. It is believed that the paintings were done by artists travelling on the Silk Road.[44]

Scientists from the Tokyo Research Institute for Cultural Properties in Japan, the Centre of Research and Restoration of the French Museums in France, the Getty Conservation Institute in the United States, and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France, analysed samples from the paintings,[45] typically less than 1 mm across.[46] They discovered that the paint contained pigments such as vermilion (red mercury sulfide) and lead white (lead carbonate). These were mixed with a range of binders, including natural resins, gums (possibly animal skin glue or egg),[46] and oils, probably derived from walnuts or poppies.[44] Specifically, researchers identified drying oils from murals showing Buddhas in vermilion robes sitting cross-legged amid palm leaves and mythical creatures as being painted in the middle of the 7th century.[43] It is believed that they are the oldest known surviving examples of oil painting, possibly predating oil painting in Europe by as much as six centuries.[44] The discovery may lead to a reassessment of works in ancient ruins in Iran, China, Pakistan, Turkey, and India.[44]

Initial suspicion that the oils might be attributable to contamination from fingers, as the touching of the painting is encouraged in Buddhist tradition,[46] was dispelled by spectroscopy and chromatography giving an unambiguous signal for the intentional use of drying oils rather than contaminants.[46] Oils were discovered underneath layers of paint, unlike surface contaminants.[46]

Scientists also found the translation of the beginning section of the original Sanskrit Pratītyasamutpāda Sutra translated by Xuanzang that spelled out the basic belief of Buddhism and said all things are transient.[47]

Attacks on the statues

[edit]Taliban incursions (1998–2001)

[edit]

During the Afghan Civil War, the area around the Buddhas was initially under the control of the Hezbe Wahdat—part of the Northern Alliance—who were against the Taliban. However, Mazar-i-Sharif fell in August 1998, and the Bamyan valley was entirely surrounded by Taliban.[48] The town was captured on 13 September 1998 after a successful blockade.[49][50]

Abdul Wahed, a local Taliban commander who had long before announced his intentions to obliterate the Buddhas, drilled holes in the Buddhas' heads into which he planned to load explosives.[51] He was prevented from proceeding by Mohammed Omar, the de facto leader of the Taliban:[51] According to United Nations representative Michael Semple:

Mullah Omar appointed Maulawi Muhammad Islam of Ru-ye Doab as Bamian governor. As a Tatar from neighbouring Samangan Province, the Maulawi had connections with all the commanders of Bamian from the jihad era. Whatever his other sins, Bamian was also a part of Maulawi Islam's heritage. His deputies described to me how, when they saw what Abdul Wahed was doing, they contacted Mullah Omar in Kandahar and he gave the order to stop further drilling.[51]

Other people blew off the head of the smaller Buddha using dynamite, aimed rockets at the larger Buddha's groin, and burnt tires at the latter's head.[51] In July 1999, Omar decreed in favour of preserving the statues, and described plans to establish a tourism circuit.[52] In early 2000, local Taliban authorities asked for the UN's assistance to rebuild drainage ditches around the tops of the alcoves where the Buddhas were set.[51]

Destruction by the Islamic Emirate

[edit]

Decision to destroy

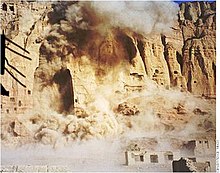

[edit]On 1 March 2001, the Taliban announced that all statues depicting humans in Afghanistan would be destroyed. Work to destroy the Buddhas began the next day, on 2 March, and continued for several weeks.[53][8] Various theories have sought to explain what prompted Taliban leader Mullah Omar to order the destruction of the statues, further complicated by seemingly shifting narratives of the events as relayed by Omar and senior Taliban officials.

On 6 March 2001, British newspaper The Times quoted Omar as stating "Muslims should be proud of smashing idols. It has given praise to Allah that we have destroyed them."[54]

During a 13 March interview for Japan's Mainichi Shimbun, Afghan Foreign Minister Wakil Ahmad Mutawakel stated that the destruction was anything but a retaliation against the international community for economic sanctions: "We are destroying the statues in accordance with Islamic law and it is purely a religious issue." A statement issued by the ministry of religious affairs of the Taliban regime justified the destruction as being in accordance with Islamic law.[55]

Later, on 18 March 2001, then Taliban ambassador-at-large Sayed Rahmatullah Hashemi said that the destruction of the statues was carried out by the Head Council of Scholars after a Swedish monuments expert proposed to restore the statues' heads. Rahmatullah Hashemi is reported as saying: "When the Afghan head council asked them to provide the money to feed the children instead of fixing the statues, they refused and said, 'No, the money is just for the statues, not for the children'. Herein, they made the decision to destroy the statues"; however, he did not comment on the claim that a foreign museum offered to "buy the Buddhist statues, the money from which could have been used to feed children".[56] Rahmatullah Hashemi added: "If we had wanted to destroy those statues, we could have done it three years ago," referring to the start of U.S. sanctions. "In our religion, if anything is harmless, we just leave it. If money is going to statues while children are dying of malnutrition next door, then that makes it harmful, and we destroy it."[57] Hashemi denied any religious grounds in the justification of the statues' destruction.[56]

In 2004, following the American invasion of Afghanistan and his exile, Omar explained in an interview:

I did not want to destroy the Bamiyan Buddha. In fact, some foreigners came to me and said they would like to conduct the repair work of the Bamiyan Buddha that had been slightly damaged due to rains. This shocked me. I thought, these callous people have no regard for thousands of living human beings—the Afghans who are dying of hunger, but they are so concerned about non-living objects like the Buddha. This was extremely deplorable. That is why I ordered its destruction. Had they come for humanitarian work, I would have never ordered the Buddha's destruction.[58]

There is additional speculation that the destruction may have been influenced by al-Qaeda in order to further isolate the Taliban from the international community, thus tightening relations between the two; however, the evidence is circumstantial.[59] Abdul Salam Zaeef held that the destruction of the Buddhas was finally ordered by Abdul Wali, the Minister for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice.[60]

International reaction

[edit]The Taliban's intention to destroy the statues, caused a wave of international horror and protest. According to UNESCO Director-General Kōichirō Matsuura, a meeting of ambassadors from the 54 member states of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC) was conducted. All OIC states—including Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, three countries that officially recognised the Taliban government—joined the protest to spare the monuments.[61] Saudi Arabia and the UAE later condemned the destruction as "savage".[62] Although India never recognised the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, New Delhi offered to arrange for the transfer of all the artifacts in question to India, "where they would be kept safely and preserved for all mankind". These overtures were rejected by the Taliban.[63] Pakistani president Pervez Musharraf sent a delegation led by Pakistan's interior minister Moinuddin Haider to Kabul to meet with Omar and try to prevent the destruction, arguing that it was un-Islamic and unprecedented.[64] As recounted by Steve Coll:

Haider quoted a verse from the Koran that said Muslims should not slander the gods of other religions. ... He cited many cases in history, especially in Egypt, where Muslims had protected the statues and art of other religions. The Buddhas in Afghanistan were older even than Islam. Thousands of Muslim soldiers had crossed Afghanistan to India over the centuries, but none of them had ever felt compelled to destroy the Buddhas. "When they have spared these statues for fifteen hundred years, all these Muslims who have passed by them, how are you a different Muslim from them?" Haider asked. "Maybe they did not have the technology to destroy them," Omar speculated.[65]

According to Taliban minister, Abdul Salam Zaeef, UNESCO sent the Taliban government 36 letters objecting to the proposed destruction. He asserted that the Chinese, Japanese, and Sri Lankan delegates were the most strident advocates for preserving the Buddhas. The Japanese in particular proposed a variety of different solutions to the issue, including moving the statues to Japan, covering the statues from view, and the payment of money.[66][67] The second edition of the Turkistan Islamic Party's magazine Islamic Turkistan contained an article on Buddhism, and described the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamyan despite attempts by the Japanese government of "infidels" to preserve the remains of the statues.[68] The exiled Dalai Lama said he was "deeply concerned".[69]

The destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas despite protests from the international community has been described by Michael Falser, a heritage expert at the Center for Transcultural Studies in Germany, as an attack by the Taliban against the globalising concept of "cultural heritage".[70] The UNESCO Director-General Kōichirō Matsuura called the destruction a "...crime against culture. It is abominable to witness the cold and calculated destruction of cultural properties which were the heritage of the Afghan people, and, indeed, of the whole of humanity."[71] Ahmad Shah Massoud, leader of the anti-Taliban resistance force, also condemned the destruction.[72]

In Rome, the former Afghan King, Mohammed Zahir Shah, denounced the declaration in a rare press statement, calling it "against the national and historic interests of the Afghan people". Zemaryalai Tarzi, who was Afghanistan's chief archeologist in the 1970s, called it an "unacceptable decision".[73]

Process of destruction

[edit]The destruction was carried out in stages. Initially, the statues were fired at for several days using anti-aircraft guns and artillery. This caused severe damage, but did not obliterate them. During the destruction, Taliban Information Minister Qudratullah Jamal said that, "The destruction work is not as easy as people would think. You can't knock down the statues by dynamite or shelling as both of them have been carved in a cliff. They are firmly attached to the mountain."[74] Later, the Taliban placed anti-tank mines at the bottom of the niches, so that when fragments of rock broke off from artillery fire, the statues would receive additional destruction from particles that set off the mines. In the end, the Taliban lowered men down the cliff face and placed explosives into holes in the Buddhas.[75] After one of the explosions failed to obliterate the face of one of the Buddhas, a rocket was launched that left a hole in the remains of the stone head.[76]

A local civilian, speaking to Voice of America in 2002, said that he and some other locals were forced to help destroy the statues. He also claimed that Pakistani and Arab engineers were involved in the destruction.[77] Mullah Omar, during the destruction, was quoted as saying, "What are you complaining about? We are only waging war on stones".[78]

Current status (2002–present)

[edit]| Pilgrimage to |

| Buddha's Holy Sites |

|---|

|

Though the figures of the two large Buddhas have been destroyed, their outlines and some features are still recognisable within the recesses. It is also still possible for visitors to explore the monks' caves and passages that connect them. As part of the international effort to rebuild Afghanistan after the Taliban war, the Japanese government and several other organisations—among them the Afghanistan Institute in Bubendorf, Switzerland, along with the ETH Zurich—have committed to rebuilding, perhaps by anastylosis, the two larger Buddhas. The local residents of Bamyan have also expressed their favour in restoring the structures.[79]

In April 2002, Afghanistan's post-Taliban leader Hamid Karzai called the destruction a "national tragedy" and pledged the Buddhas to be rebuilt.[80] He later called the reconstruction a "cultural imperative".[78]

In September 2005, Mawlawi Mohammed Islam Mohammadi, Taliban governor of Bamyan province at the time of the destruction and widely seen as responsible for its occurrence, was elected to the Afghan Parliament. He blamed the decision to destroy the Buddhas on Al-Qaeda's influence on the Taliban.[81] In January 2007, he was assassinated in Kabul.

Swiss filmmaker Christian Frei made a 95-minute documentary titled The Giant Buddhas on the statues, the international reactions to their destruction, and an overview of the controversy, released in March 2006. Testimony by local Afghans validates that Osama bin Laden ordered the destruction and that, initially, Mullah Omar and the Afghans in Bamyan opposed it.[82]

Since 2002, international funding has supported recovery and stabilisation efforts at the site. Fragments of the statues are documented and stored with special attention given to securing the structure of the statue still in place. It is hoped that, in the future, partial anastylosis can be conducted with the remaining fragments. In 2009, ICOMOS constructed scaffolding within the niche to further conservation and stabilization. Nonetheless, several serious conservation and safety issues exist and the Buddhas are still listed as World Heritage in Danger.[83]

In the summer of 2006, Afghan officials were deciding on the timetable for the re-construction of the statues. As they waited for the Afghan government and international community to decide when to rebuild them, a $1.3 million UNESCO-funded project was sorting out the chunks of clay and plaster—ranging from boulders weighing several tons to fragments the size of tennis balls—and sheltering them from the elements.

The Buddhist remnants at Bamyan were included on the 2008 World Monuments Watch List of the 100 Most Endangered Sites by the World Monuments Fund.

In 2013, the foot section of the smaller Buddha was rebuilt with iron rods, bricks and concrete by the German branch of ICOMOS.[84] Further constructions were halted by order of UNESCO, on the grounds that the work was conducted without the organisation's knowledge or approval. The effort was contrary to UNESCO's policy of using original material for reconstructions, and it has been pointed out that it was done based on assumptions.[85][86]

In 2015, a wealthy Chinese couple, Janson Hu and Liyan Yu, financed the creation of a Statue of Liberty-size 3D light projection of an artist's view of what the larger Buddha, known as Solsol to locals, might have looked like in its prime. The image was beamed into the niche one night in 2015; later the couple donated their $120,000 projector to the culture ministry.[87][88]

Shortly after the 2021 Taliban offensive that saw the overthrow of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan and the return of Taliban to the government, tourists were again granted permission to visit the site. While the Taliban promised to preserve the Bamyan valley, preservation work was ceased indefinitely.[89] UNESCO's Afghan operations were stymied, largely due to foreign investors' fears that continued support of cultural preservation projects in the country would run afoul of international sanctions. In February 2023, UNESCO's restoration work resumed when the Italian government approved new funding.[90]

Restoration

[edit]

The UNESCO Expert Working Group on Afghan cultural projects convened to discuss what to do about the two statues between 3–4 March 2011 in Paris. Researcher Erwin Emmerling of Technical University Munich announced he believed it would be possible to restore the smaller statue using an organic silicon compound.[91] The Paris conference issued a list of 39 recommendations for the safeguarding of the Bamyan site. These included leaving the larger Western niche empty as a monument to the destruction of the Buddhas, a feasibility study into the rebuilding of the Eastern Buddha, and the construction of a central museum and several smaller site museums.[92] Work has since begun on restoring the Buddhas using the process of anastylosis, where original elements are combined with modern material. It is estimated that roughly half the pieces of the Buddhas can be put back together according to Bert Praxenthaler, a German art historian and sculptor involved in the restoration. The restoration of the caves and Buddhas has also involved training and employing local people as stone carvers.[93] The project, which also aims to encourage tourism to the area, is being organised by UNESCO and the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS).

The work has come under some criticism. It is felt by some, such as human rights activist Abdullah Hamadi, that the empty niches should be left as monuments to the fanaticism of the Taliban, while others believe the money could be better spent on housing and electricity for the region.[94] Some people, including Habiba Sarabi, the provincial governor, believe that rebuilding the Buddhas would increase tourism, which would aid the surrounding communities.[94]

Rise of the Buddhas with 3D light projection

[edit]After fourteen years, on 7 June 2015, a Chinese adventurist couple Zhang Xinyu and Liang Hong filled the empty cavities where the Buddhas once stood with 3D laser light projection technology. The projector used for the installation, worth approximately $120,000, was donated by Zhang and Liang, who were saddened by the destruction of the statues. With the desire of paying tribute, they requested permission from UNESCO and the Afghan government to do the project. About 150 local people came out to see the unveiling of the holographic statues.[95][96]

Replicas

[edit]

The destruction of the Buddhas of Bamyan inspired attempts to construct replicas of the Bamyan Buddhas.[97] These include the following.

- In 2001 in China, carving of a 37 metres (121 ft) high Buddha was initiated in Sichuan, which is the same height as the smaller of the two Bamiyan Buddhas. It was funded by a Chinese businessman, Liang Simian.[98] The project appears to have been given up for unknown reasons.[99]

- In Sri Lanka, a full-scale replica has been created, which is now known as the Tsunami Honganji Viharaya at Pareliya. It is dedicated to the victims of the 2005 tsunami in the presence of Mahinda Rajapaksha. It was funded by Japan's Hongan-ji Temple of Kyoto and was inaugurated in 2006.[100]

- In Poland, the Arkady Fiedler Museum of Tolerance has a replica of a Bamiyan Buddha.[101]

- An 80 feet (24 m) stone Buddha was inaugurated at Sarnath in India in 2011. It stands within the Thai Buddhist Vihara.[102][103]

Gallery

[edit]-

Taller Buddha, after destruction

-

Smaller Buddha, after destruction

-

View of the rock where monasteries and Buddhas are carved

-

The landscape of the archaeological Remains of the Bamyan Valley

In popular culture

[edit]In the 2012 video game, Call of Duty: Black Ops 2, these statues can be seen during the opening segment of the story mode mission, "Old Wounds".

Despite the Buddhas's destruction, the ruins continue to be a popular culture landmark,[104] bolstered by increasing domestic and international tourism to the Bamyan Valley.[105] The area around the ruins has since been used for the traditional game of buzkashi,[106] and other events. The music video of pop singer Aryana Sayeed's hit 2015 song "Yaar-e Bamyani" was also shot by the ruins.[107] The statues inspired Islamic writers in historical times. The larger statue appears as the malevolent giant Salsal in medieval Turkish tales.[108]

In June 1971, Empress Michiko of Japan visited the Buddhas during an Imperial state visit to the Kingdom of Afghanistan with her husband. Upon her return to Japan, she composed a waka poem.[109]

A 2012 novel by Rajesh Talwar titled An Afghan Winter provides a fictional backdrop to the destruction of the Buddhas and its impact on the global Buddhist community.[110]

The 2022 Indian film Ram Setu shows the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan and an archaeological team's subsequent attempts to salvage the remains where they discover a fictional treasure belonging to Raja Dahir and a colossal reclining Buddha (which has been described in the writings of Xuanzang but has not actually been discovered).[111][112]

The AD 507 chapter of 2020 novel A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne writes an imaginary account of how the Buddhas were commissioned and built.[113]

See also

[edit]- Buddha Collapsed out of Shame

- Destruction of art in Afghanistan

- Buddhism in Afghanistan

- Buddhism in Central Asia

- Aniconism

- Aniconism in Islam

- Iconoclasm

- Destruction of cultural heritage by the Islamic State

- Greco-Buddhism

- Index of Buddhism-related articles

- Islamist destruction of Timbuktu heritage sites

- List of colossal sculptures in situ

- List of destroyed heritage

- Ancient history of Afghanistan

- Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

- List of World Heritage in Danger

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Blänsdorf, Catharina; et al. (2009). "Dating of the Buddha Statues – AMS 14C Dating of Organic Materials". Monuments and Sites. 19: 231–236.

- ^ a b c d Petzet, Michael, ed. (2009). The Giant Buddhas of Bamiyan. Safeguarding the remains (PDF). ICOMOS. pp. 18–19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ Gall, Carlotta (5 December 2006). "Afghans consider rebuilding Bamiyan Buddhas". International Herald Tribune/The New York Times. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ a b c Eastern Buddha: 549–579 CE (1 σ range, 68.2% probability) 544–595 CE (2 σ range, 95.4% probability). Western Buddha: 605–633 CE (1 σ range, 68.2%) 591–644 CE (2 σ range, 95.4% probability). In Blänsdorf et al. (2009).

- ^ a b c Nicholson, Oliver (19 April 2018). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. p. 708. ISBN 978-0-19-256246-3.

The Bamiyan Buddhas dated from Hephthalite times

- ^ "Taliban make ancient Buddhas they destroyed into a tourist attraction". NBC News. 24 November 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ^ Morgan, Llewelyn (2012). The Buddhas of Bamiyan. Harvard University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-674-06538-3.

- ^ a b Shah, Amir (3 March 2001). "Taliban destroy ancient Buddhist relics – International pleas ignored by Afghanistan's Islamic fundamentalist leaders". The Independent. Archived from the original on 6 January 2011.

- ^ Morgan, Kenneth W (1956). The Path of the Buddha. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 43. ISBN 978-8120800304. Retrieved 2 June 2009 – via Google Books.

- ^ "booklet web E.indd" (PDF). Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "Visit Bamiyan". Bamiyanculturalcentre.org. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ a b Gall, Carlotta (6 December 2006). "From Ruins of Afghan Buddhas, a History Grows". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ^ "Bamiyan and Buddhism Afghanistan". Depts.washington.edu. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Remembering Bamiyan". Kashgar.com.au. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ Jain, Meenakshi (2019). Flight of Deities and Rebirth of Temples: Episodes from Indian History. Aryan Books International. p. 28. ISBN 978-81-7305-619-2.

- ^ "Bamiyan and Buddhism Afghanistan". Depts.washington.edu. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Higuchi, Takayasu; Barnes, Gina (1995). "Bamiyan: Buddhist Cave Temples in Afghanistan". World Archaeology. 27 (2): 299. doi:10.1080/00438243.1995.9980308. ISSN 0043-8243. JSTOR 125086.

- ^ Gruen, Armin; Remondino, Fabio (September 2004). "Photogrammetric Reconstruction of the Great Buddha of Bamiyan, Afghanistan". The Photogrammetric Record: 182, Fig.5.

- ^ a b Heirman, Ann; Bumbacher, Stephan Peter (11 May 2007). The Spread of Buddhism. BRILL. p. 88. ISBN 978-90-04-15830-6.

The Great Buddhas of Bamiyan were erected under the Hephthalites

- ^ "The White Huns – The Hephthalites". Silkroad Foundation. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ Research of state and stability of the rock niches of the Buddhas of Bamiyan in "Completed Research Results of Military University of Munich" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Computer Reconstruction and Modeling of the Great Buddha Statue in Bamiyan, Afghanistan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Mount Emei Scenic Area, including Leshan Giant Buddha Scenic Area". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "Cultural Landscape and Archaeological Remains of the Bamiyan Valley" (PDF). UNESCO. 2003.

- ^ "Bamiyan Buddhas Once Glowed in Red, White and Blue". Sciencedaily.com. 25 February 2011. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ Yamada, Meiji (1 January 2002). "Buddhism of Bamiyan" (PDF). Pacific World, Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies. 3rd. 4: 109–122. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2010.

- ^ "Bamiyan and Buddhist Afghanistan". Depts.washington.edu. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Xuan Zang and the Third Buddha". Laputanlogic.com. 9 March 2007. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ Sauer, Eberhard (5 June 2017). Sasanian Persia: Between Rome and the Steppes of Eurasia. Edinburgh University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-1-4744-2068-6.

- ^ a b c Alram, Michael; Filigenzi, Anna; Kinberger, Michaela; Nell, Daniel; Pfisterer, Matthias; Vondrovec, Klaus. "The Countenance of the other (The Coins of the Huns and Western Turks in Central Asia and India) 2012-2013 exhibit: 14. Kabulistan and Bactria at the Time of 'Khorasan Tegin Shah'". Pro.geo.univie.ac.at. Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ^ Margottini, Claudio (20 September 2013). After the Destruction of Giant Buddha Statues in Bamiyan (Afghanistan) in 2001: A UNESCO's Emergency Activity for the Recovering and Rehabilitation of Cliff and Niches. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-3-642-30051-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Margottini, Claudio (20 September 2013). After the Destruction of Giant Buddha Statues in Bamiyan (Afghanistan) in 2001: A UNESCO's Emergency Activity for the Recovering and Rehabilitation of Cliff and Niches. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-3-642-30051-6.

- ^ Rhie, Marylin Martin (15 July 2019). Early Buddhist Art of China and Central Asia, Volume 2 The Eastern Chin and Sixteen Kingdoms Period in China and Tumshuk, Kucha and Karashahr in Central Asia (2 vols). BRILL. p. 668. ISBN 978-90-04-39186-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Margottini, Claudio (20 September 2013). After the Destruction of Giant Buddha Statues in Bamiyan (Afghanistan) in 2001: A UNESCO's Emergency Activity for the Recovering and Rehabilitation of Cliff and Niches. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 8–15. ISBN 978-3-642-30051-6.

- ^ a b c >"A striking parallel to the Balalyk tepe murals is offered by files of donors represented on the right and left walls of the vault of the 34 m Buddha at Bamiyan. (...) The remarkable overall stylistic and iconographic resemblance between the two sets of paintings would argue for their association with the artistic tradition of the Hephthalite ruling classes of Tukharestan that survived the downfall of Hephthalite power in A.D. 577" in "Azarpay, Guitty; Belenickij, Aleksandr M.; Maršak, Boris Il'ič; Dresden, Mark J. (January 1981). Sogdian Painting: The Pictorial Epic in Oriental Art. University of California Press. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-0-520-03765-6.

- ^ a b c "Seizing large areas, the Hephthalites met with various kinds of art and of course, to some extent, acted as intermediary in the transfer of artistic traditions of one nation to another. It is here, in the opinion of Albaum, that the similarity of some of the figures in paintings from Balalyk-tepe and those from Bamiyan must be sought, which then was part of the Hephthalite state. Such similarities are exemplified by the right side triangular lapel, hair accessories and some ornamental motifs." in Kurbanov, Aydogdy (2010). "The Hephthalites: Archaeological and Historical Analysis" (PDF): 67.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Azarpay, Guitty; Belenickij, Aleksandr M.; Maršak, Boris Il'ič; Dresden, Mark J. (1 January 1981). Sogdian Painting: The Pictorial Epic in Oriental Art. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03765-6.

- ^ "The globelike crown of the princely donor has parallels in Sasanian coin portraits. Both this donor and the Buddha at the left are adorned with hair ribbons or kusti, again borrowed the Sasanian royal regalia" in Rowland, Benjamin (1975). The art of Central Asia. New York: Crown. p. 88.

- ^ a b c Bosworth also says that the "Ephthalites were incapable of such work" in Bosworth, C. Edmund (15 May 2017). The Turks in the Early Islamic World. Routledge. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-351-88087-9.

- ^ a b "Lost, Stolen, and Damaged Images: The Buddhist Caves of Bamiyan". huntingtonarchive.org.

- ^ Rowland, Benjamin. The Art of Central Asia (Art of the World) | Central Asia | Silk Road. p. 103. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ Kurbanov, Aydogdy (2013). "Some information related to the Art History of the Hephthalites". Isimu. 16: 106, note 42.

- ^ a b "Scientists discover first-ever oil paintings in Afghanistan". Earthtimes.org. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 24 April 2008.

- ^ a b c d Highfield, Roger (22 April 2008). "Oil painting invented in Asia, not Europe". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 23 April 2008. Retrieved 24 April 2008. However, the press release picked up by media, clearly misdates the earliest uses of oil paint in Europe, which is fully described in a treatise by Theophilus Presbyter of 1100–1120, and may date back to the Ancient Romans. See: Rutherford John Gettens, George Leslie Stout, 1966, Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-21597-0 Painting Materials: A Short Encyclopedia (online text), p. 42 "Bibliotheca Augustana". Archived from the original on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

- ^ "Ancient Buddhist Paintings From Bamyan Were Made of Oil, Hundreds of Years Before Technique Was 'Invented' In Europe". Sciencedaily.com. Retrieved 24 April 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Ball, Philip (2008). "Ancient Buddhas painted in oils". Nature. nature.com. doi:10.1038/news.2008.770. Retrieved 24 April 2008.

- ^ "Secret sutra found in rubble of Bamiyan Buddha". Buddhistchannel.tv. 12 November 2006. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "Aid staff flee Taliban shells". The Independent. 13 August 1998. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "BBC News | South Asia | Taleban take opposition stronghold". BBC News.

- ^ "Taliban tanks and artillery fire on Buddhas". The Daily Telegraph. 3 March 2001. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Semple, Michael (2 March 2011). "Guest Blog: Why the Buddhas of Bamian were destroyed". Afghanistan Analysts Network - English (in Pashto). Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ Harding, Luke (3 March 2001). "How the Buddha got his wounds". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 28 February 2006. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- ^ Domingo, Plácido (December 2016). "End the International Destruction of Cultural Heritage". Vigilo (48). Din l-Art Ħelwa: National Trust of Malta: 30–31. ISSN 1026-132X.

- ^ Markos Moulitsas Zúniga (2010). American Taliban: How War, Sex, Sin, and Power Bind Jihadists and the Radical Right. Polipoint Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-936227-02-0.

Muslims should be proud of smashing idols.

- ^ "Destruction of Giant Buddhas Confirmed". AFP. 12 March 2001. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ^ a b Kassaimah, Sahar (12 January 2001). "Afghani Ambassador Speaks at USC". IslamOnline. Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ^ Crossette, Barbara (19 March 2001). "Taliban Explains Buddha Demolition". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ^ Mohammad Shehzad (3 March 2001). "The Rediff Interview/Mullah Omar". The Rediff. Kabul. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ^ Tarzi, Amin (2008). The Taliban and the crisis of Afghanistan. Robert D. Crews, Amin Tarzi. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. pp. 305–306. ISBN 978-0-674-03002-2. OCLC 456412511.

- ^ Zaeef p. 126

- ^ "World appeals to Taliban to stop destroying statues". CNN. 3 March 2001. Archived from the original on 24 December 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ^ Bearak, Barry (4 March 2001). "Over World Protests, Taliban Are Destroying Ancient Buddhas". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2008.

- ^ "General Assembly 'Appalled' By Edict on Destruction of Afghan Shrines; Strongly Urges Taliban To Halt Implementation". Un.org. 2 January 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ Zaeef, Abdul Salam, My Life with the Taliban eds Alex Strick van Linschoten and Felix Kuehn, p. 120, C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd, ISBN 1-84904-026-5

- ^ Coll, Steve (2004). Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001. Penguin Group. pp. 554–555. ISBN 9781594200076.

- ^ Abdul Salam Zaeef (2011). My Life with the Taliban. Oxford University Press. pp. 127–. ISBN 978-1-84904-152-2.

- ^ "Japan offered to hide Bamiyan statues, but Taliban asked Japan to convert to Islam instead". Japan Today. 27 February 2010.

- ^ محمد ضياء الرحمن الأعظمي (November 2008). "الدبانا البوذية" (PDF). تركستان الإسلامية. No. السنة الأولى: العدد الثاني. pp. 46–49. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2017.

- ^ "Bamiyan statues: World reaction". 5 March 2001.

- ^ Falser, Michael. "The Bamiyan Buddhas, performative iconoclasm and the 'image' of heritage". In: Giometti, Simone; Tomaszewski, Andrzej (eds.): The Image of Heritage. Changing Perception, Permanent Responsibilities. Proceedings of the International Conference of the ICOMOS International Scientific Committee for the Theory and the Philosophy of Conservation and Restoration. 6–8 March 2009 Florence, Italy. Firenze 2011: 157–169.

- ^ "U.N. Confirms Destruction of Afghan Buddhas". ABC News. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Ahmad Shah Massoud". The Telegraph. 16 September 2001. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ ""An attempt to wipe out history": The destruction of the Bamian Buddha colossi in 2001". March 2015.

- ^ "Photos document destruction of Afghan Buddhas". Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ "Destruction and Rebuilding of the Bamyan Buddhas". Slate Magazine.

- ^ Bergen, Peter. "The Osama bin Laden I Know", 2006. p. 271

- ^ "Local People Regret Taleban Destroyed Buddha Statues". VOA. 11 February 2002.

- ^ a b "Rebuilding the Bamiyan Buddhas". Slate.com. 23 July 2004.

- ^ "Disputes damage hopes of rebuilding Afghanistan's Bamiyan Buddhas". TheGuardian.com. 10 January 2015.

- ^ "Karzai pledges to rebuild Afghan Buddhas". CNN. 9 April 2002.

- ^ Focus on Terrorism, Volume 8 by Edward V. Linden

- ^ "Laden ordered Bamyan Buddha destruction". The Times of India. 28 March 2006. Archived from the original on 6 May 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ^ Petzet, Michael (2010). "Safeguarding the Buddhas of Bamiyan". In Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet and John Ziesemer (Eds.), "Heritage at Risk: ICOMOS World Report 2008–2010 on Monuments and Sites in Danger" (PDF). Berlin: hendrik Bäßler verlag, 2010.

- ^ Martini, Alessandro; Rivetti, Ermanno (6 February 2014). "Organisation says actions of German archaeologists who have partially rebuilt one of the statues 'border on the criminal'". The Art Newspaper. Archived from the original on 15 January 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ Bobin, Frédéric (10 January 2015). "Disputes damage hopes of rebuilding Afghanistan's Bamiyan Buddhas". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ "タリバン破壊のバーミヤン遺跡、ドイツ隊が勝手に足復元 ユネスコが撤去勧告も". The Sankei Shimbun (in Japanese). 18 May 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ Nordland, Rod (18 June 2019). "2 Giant Buddhas Survived 1,500 Years. Fragments, Graffiti and a Hologram Remain". The New York Times.

- ^ "Chinese couple bring destroyed Bamiyan Buddha statue back to 'light'". The Express Tribune. 13 June 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "Taliban make ancient Buddhas they destroyed into a tourist attraction". NBC News. 24 November 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ Geranpayeh, Sarvy (21 April 2023). "Italy throws Afghanistan a lifeline for restoration in the Bamiyan area". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ "Bamiyan Buddhas once glowed in red, white and blue". Technical University of Munich. 25 February 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "Expert Working Group releases recommendations for Safeguarding Bamiyan". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ Graham-Harison, Emma (16 May 2012). "Stone carvers defy Taliban to return to the Bamiyan valley". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Kakissis, Joanna (27 July 2011). "Bit By Bit, Afghanistan Rebuilds Buddhist Statues". National Public Radio. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ Mary-Ann Russon (12 June 2015). "Afghanistan: Buddhas of Bamiyan resurrected as laser projections". International Business Times. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ^ Paula Mejia (15 June 2015). "Afghanistan Buddha Statues Destroyed by Taliban Reimagined as Holograms". News Week. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ^ The Transformative Power of the Copy, Jul 27, 2017

- ^ "Buddha rises again". 5 October 2001. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ Leshan – The disappearance of a kitsch replica in "The Giant Buddhas, Documentary", Switzerland 2005, Christian Frei

- ^ "Sun, sand and surf". Sunday Observer. Associated Newspapers of Ceylon Limited. 14 January 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ Dritanje (23 September 2013). "Rivertrain: The Buddhas of Bamiyan". Rivertrain. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Sarnath gets country's tallest statue of Lord Buddha". The Times of India. 16 March 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ Chakraborty, Tapas (1 November 2009). "Sarnath set to scale heights - 100-foot buddha statue being built in gandhara style". Telegraph India. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "The return of Afghanistan's Buddhas". The Atlantic. 10 June 2015. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ Bamyani, Zafar (26 May 2015). "Tourism Revives in the Land of the Blasted Buddhas". RFE/RL. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ "Stars inspire young fans in peaceful Afghan town". Cricketworldcup.com. 29 December 2018. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ "Newsletter for the Embassy of Afghanistan in Japan (Volume 1, Issue 1)" (PDF). The Heart of Asia Herald. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ Laban Kaptein, Eindtijd en Antichrist, p. 127. Leiden 1997. ISBN 90-73782-89-9

- ^ "Waka Poems: 2001 - The Imperial Household Agency". Kunaicho.go.jp. 30 April 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Rajesh Talwar. "An Afghan Winter". Kirkus Reviews.

- ^ Kumar, Anuj (26 October 2022). "'Ram Setu' movie review: A bridge too far to cross for Akshay Kumar". The Hindu.

- ^ Bamiyan at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom. 3 June 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Cloonan, Michele V. "The Paradox of Preservation", Library Trends, Summer 2007.

- Braj Basi Lal; R. Sengupta (2008). A Report on the Preservation of Buddhist Monuments at Bamiyan in Afghanistan. Islamic Wonders Bureau. ISBN 978-81-87763-66-6.

- Kassaimah, Sahar. "Afghani Ambassador Speaks At USC", IslamOnline, 12 March 2001.

- Maniscalco, Fabio. World Heritage and War, monographic series "Mediterraneum", vol. 6, Naples 2007, Massa Publisher "Catalogo: Mediterraneum". Massa Editore. Archived from the original on 31 December 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- Noyes, James. "Bamiyan Ten Years On: What this Anniversary tells us about the New Global Iconoclasm", "Telos", 1 March 2010.

- Tarzi, Zemaryalai. L'architecture et le décors rupestre des grottes de Bamiyan ISBN 978-2-7200-0180-2

- Weber, Olivier, The Assassinated Memory (Mille et Une Nuits, 2001)

- Weber, Olivier, Tha Afghan Hawk: travel in the country of talibans (Robert Laffont, 2001)

- Weber, Olivier, On the Silk Roads (with Reza, Hoëbeke, 2007)

- Wriggins, Sally Hovey. Xuanzang: A Buddhist Pilgrim on the Silk Road. Boulder: Westview Press, 1996

- "Afghan who had statues destroyed killed". Archived from the original on 28 January 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- "Afghanistan 1969–1974: February 2001"

- "Artist to recreate Afghan Buddhas". BBC News, 9 August 2005.

- "Bamian Buddha Statues and Theosophy"

- "Pakistani, Saudi engineers helped destroy Buddhas" Daily Times, Sunday, 19 March 2006.

- "The Rediff Interview/Mullah Omar, 12 April 2004"

External links

[edit]- Japan offered to hide Bamiyan statues, but Taliban asked Japan to convert to Islam instead

- News articles about the Buddhas of Bamyan

- Photos of the Buddhas of Bamyan

- Bamyan Afghanistan Laser Project

- World Heritage Tour: 360 degree image (after destruction)

- Bamyan Development Community Portal for cultural heritage management of Bamyan

- The World Monuments Fund's Watch List 2008 listing for Bamyan

- Historic Footage of Bamyan Statues, c. 1973 on YouTube

- The Valley of Bamiyan A tourist pamphlet from 1967

- Researchers Say They Can Restore 1 of Destroyed Bamiyan Buddhas

- Secrets of the Bamiyan Buddhas, CNRS

- Bamiyan photo gallery, UNESCO

- Secrets of Bamiyan Buddhist murals. ESRF

- Photo Feature Covering Bamiyan Site

- 6th-century religious buildings and structures

- Colossal Buddha statues

- Arts in Afghanistan

- Central Asian Buddhist sites

- 2001 in religion

- 2001 in Afghanistan

- 6th-century Buddhism

- Afghan Civil War (1996–2001)

- Anti-Buddhism

- Archaeological sites in Afghanistan

- Bamyan Province

- Buddha statues

- Buddhism in Afghanistan

- Buddhist art

- Buddhist pilgrimage sites in Afghanistan

- Buildings and structures demolished in 2001

- Demolished buildings and structures in Afghanistan

- Destroyed sculptures

- Hazarajat

- Iconoclasm

- Rock art in Asia

- Silk Road

- Taliban

- Tourist attractions in Afghanistan

- Vandalized works of art

- World Heritage Sites in Afghanistan

- World Heritage Sites in Danger

- Removed statues

- Persecution of Buddhists by Muslims

- Stone Buddha statues

- Former religious buildings and structures in Afghanistan

- War crimes in Afghanistan

- Monuments and memorials in Afghanistan

![Mural of the Sun God riding his golden chariot and rows of royal donors along the sides, over the head of the smaller 38 meter Eastern Buddha (carbon-dated to 544–595 CE).[1][2]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/88/Mural_of_the_Sun_God_riding_his_golden_chariot%2C_over_the_head_of_the_smaller_38_meter_Eastern_Buddha.jpg/200px-Mural_of_the_Sun_God_riding_his_golden_chariot%2C_over_the_head_of_the_smaller_38_meter_Eastern_Buddha.jpg)

![Probable King of Bamyan, in Sasanian style, in the niche of the 38 meters Buddha, next to the Sun God, Bamyan.[30][32][38]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5f/Painting_of_a_King_in_the_niche_of_the_38_meter_Buddha%2C_Bamiyan.jpg/154px-Painting_of_a_King_in_the_niche_of_the_38_meter_Buddha%2C_Bamiyan.jpg)

![Probable Hepthalite rulers of Tokharistan, with single-lapel caftan and single-crescent crown, in the lateral row of dignitaries next to the Sun God.[35][36][32]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f2/Hephthalite_sponsors_at_Bamiyan_%28ceiling_of_the_38_meter_Buddha%2C_detail_of_royal_sponsors%2C_enhanced%29.jpg/200px-Hephthalite_sponsors_at_Bamiyan_%28ceiling_of_the_38_meter_Buddha%2C_detail_of_royal_sponsors%2C_enhanced%29.jpg)

![Western Buddha, Niche, ceiling, east section E1 and E2.[40]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0c/Bamiyan_Western_Buddha%2C_Niche%2C_ceiling%2C_east_section_E1_and_E2.jpg/159px-Bamiyan_Western_Buddha%2C_Niche%2C_ceiling%2C_east_section_E1_and_E2.jpg)

![Devotee in double-lapel caftan, left wall of the niche of the Western Buddha.[40][41] He has also been described as a Hephthalite.[42]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Bamiyan_devotee_in_double-lapel_caftan.jpg/141px-Bamiyan_devotee_in_double-lapel_caftan.jpg)